Sniffing the Past is delighted to host a guest blog from Jane Hamlett, Lesley Hoskins and Rebecca Preston from the AHRC-funded project Pets and Family Life in England and Wales 1837-1839

In the first decades of the twentieth century there were more places than ever before to buy a dog in London. Markets and some shops dealing with animals had been long established, but more specialist animal shops emerged and ‘Zoological Departments’ became a feature of smart department stores.

Yet, acquiring a dog, for money, remained an uncomfortable process, and writers of advice on pet keeping stressed the perils of such transactions.

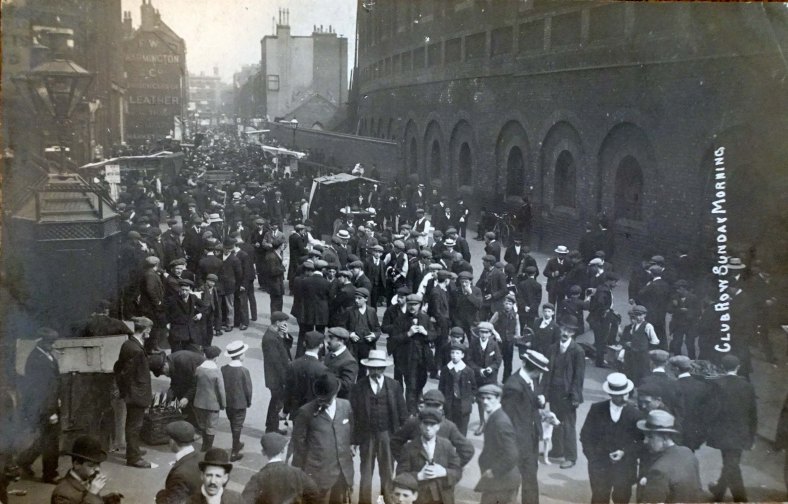

Postcard view posted in September 1908 showing the entrance to Sclater Street on Sunday morning, where the dog dealers congregated in the shadow of the Bishopsgate goods depot (top right).

This blog explores why, despite demand, and a growing range of sellers, the British were unable to fully embrace buying dogs. In an era that saw a rapid expansion in modern consumer culture, why was it that dogs were never entirely viewed as commodities?

There were of course all kinds of ways in which it was possible to get a dog – through personal networks, dog shows or even from newly founded dog homes.

In the nineteenth-century the writers of advice manuals on how to care for pets devoted plenty of space to dogs – hailing them as the most important pet. But acquiring them for cash was fraught with difficulty.

There were a few options available – visiting an animal dealer’s shop or an animal market, buying through a small ad, or purchasing at a show or through a breeder.

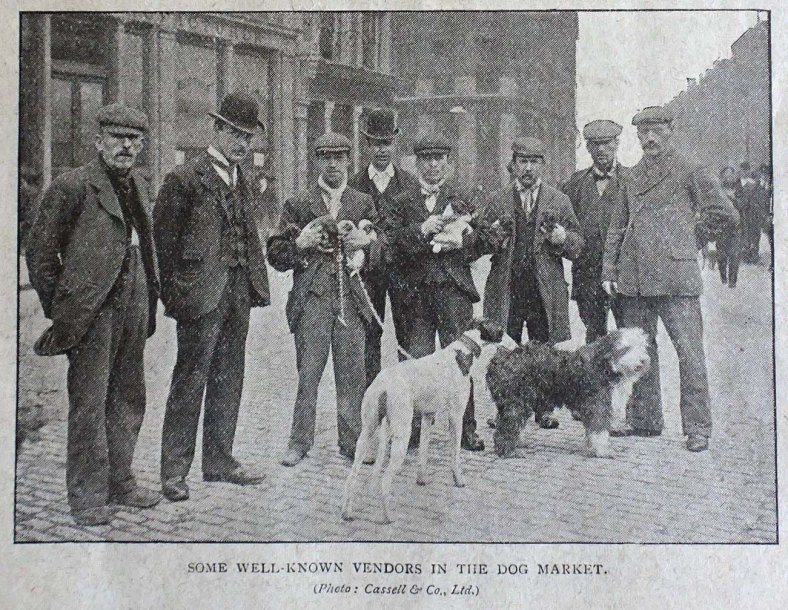

Dogs dealers in Bethnal Green Road near the junction with Sclater Street. From Cassell’s New Penny Magazine, No. 161, Vol. XIII, 1902, p. 161.

Markets and animal shops were viewed with suspicion. At Club Row, Bethnal Green, one of the capital’s best-known animal markets in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the dealing in dogs and other animals became almost a spectator sport for middle- and upper-class social commentators. Alternately fascinated and horrified by the trade in live creatures, their observations on animal cruelty and hygiene were riven with class prejudice about the dealers and the streets where they lived and worked .

Pet shops were also seen as potentially hazardous. Pets for Boys and Girls (1923) worried that these shops might not be clean and that their dogs were therefore more vulnerable to disease; it stressed the need to go to a dealer of high repute.

There were mixed views on classified ads. The Practical Kennel (1877) suggested that buying from ads was only advisable if the breeder was already well known. Such criticisms had a clear class dimension. Readers of Cassell’s Book of the Home were warned: “never trust ads in lower class edition papers”.

In his expansive Our Friend the Dog (1895) the loquacious Gordon Stables went into more detail on this matter and devoted a chapter to buying and selling dogs. He suggests that it was acceptable to advertise in the specialist press, listing The Field, The Stockkeeper and Exchange and Mart. However, he suggested the best way was to contact a “respectable breeder” and to get a local vet to check the animal out.

The Boys’ Own Book of Pets and Hobbies (1912) was more positive about the advertisement system, suggesting that this was the best method of purchase for ordinary buyers. From the late 1860s, Exchange and Mart’s small ads offered dogs of all types for sale or exchange from breeders as well as private individuals. Sometimes the dogs could be visited before purchase or were offered on approval. But it could be a risky business and the magazine instituted a deposit system to help prevent fraud.

But even dog shows, presumably less problematic because they were adjudicated by judges using “breed standards”, were a potentially hazardous and sometimes exploitative place for a non-specialist to buy.

Nonetheless, from the turn of the century there were an increasing number of places one could buy a dog in the metropolis.

From the late nineteenth century, London saw a growth in department stores – that encouraged a new kind of shopping based on spectacle and display.

Animals were seen as a good mean of luring consumers (especially women with children) into the stores. From 1885 the department store Whiteley’s advertised a “Zoological Department”. The catalogue was prefaced with an extensive list of foreign birds, but dogs (pet, sporting and watch) also featured.

These zoological departments were to become common features of department stores in the early twentieth century (we have found evidence for Whiteley’s, Harrods, Selfridges, the Army and Navy Stores, and Gamages).

The departments were marketed as distinctly modern spaces, where animals were kept in spacious, clean and orderly conditions – the antithesis of the negative stereotypes of pet shops and animal dealers’ stores.

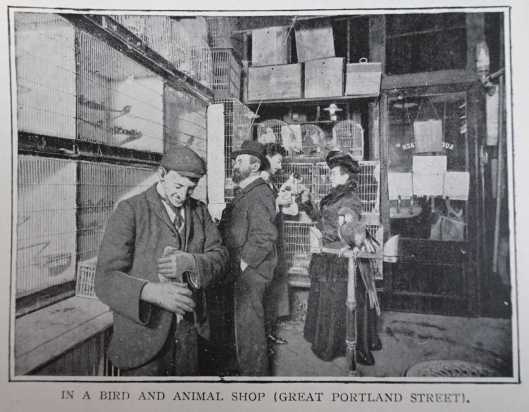

But large animal shops were also becoming more established landmarks in London’s retail landscape. Newcomers included Chapman’s of Tottenham Court Road, Augustus Zache’s Portland Street shop that was documented in George Sim’s photo magazine Living London and Palmer’s of Camden, established in the 1920s.

An image from George Sim’s Living London, possibly showing Augustus Zache’s Portland Street pet shop.

A notable London pet dealer who became increasing established was James Willson – whose business Willson’s Livestock Providers Ltd. operated from Goodge Street in the late nineteenth century and was established at 37 New Oxford Street by about 1900. In the 1920s stock included dogs, birds, poultry and Persian cats.

Willson’s seems to have placed a particular emphasis on dogs – and to have used publicity to try and offset consumer worries about their purchase.

A 1916 ad for the shop declared: “All our adult dogs are sold on 14 days’ trial on condition that if not liked they will be exchanged for livestock to value from our stock within this period. All our dogs are daily inspected by a Qualified Veterinary Surgeon.”

A 1922 article in Ideal Home magazine advised that Willson’s offered personal selection and exchange – emphasizing the importance of the bond between individual dog and owner:

“Do you require a dog? If you do, I can tell you that you will get exceptional value at moderate price from Willson’s establishment at 37, New Oxford Street. Here you cannot only select your dog personally, but one will be sent to your address in accordance with your requirements, and if it proves unsuitable, will be exchanged for another. This Mr Willson undertakes to do until you are satisfied! Dogs of all kinds may be had for £1 upwards – a thoroughly trained house-dog for £5 is a speciality. The following photograph shows one of the fashionable (pedigree) wolfhounds.”

Despite the growing sophistication of the shops – and marketing strategies that were clearly designed to overcome the stereotype of the irresponsible animal seller, twentieth-century dog lovers were unable to overcome a lingering view that a dog was not something that should be purchased over the counter.

In a 1925 issue of Ideal Home, an article on ‘Dogs and the Home’ expressed the feeling that this was simply not the right way to go about getting a dog: “A dog is a person, not a piece of merchandise to be bought over the shop counter. Go to the breeder, if possible; choose your dog from the home in which he was reared, observing closely the conditions he had known til now. …”

Pets for Young People (1938) stressed that shop-bought dogs were a bad idea – not just on grounds of pedigree, but because it was difficult to tell what the temperament of the parents had been: “If you buy a young mongrel at a shop you will probably never discover who his parents were. They may have been very intelligent and good tempered – or just the reverse. And so, when you buy a young mongrel you run the risk of being sadly disappointed with him when he grows up. You do not run that risk when you buy a thoroughbred dog from the man who owns the dog’s mother.”

Thus, while there was a range of new ways of buying a dog from a reputable source by the early twentieth century, a reluctance to acquire them from shops continued. The qualities ascribed to dogs and their emotional attachment to humans rendered the very act of purchase problematic – there was an idea that it was inappropriate to subject them to commercial transactions. But, in addition, ideas of social hierarchy, class and lineage played a role.

Click here to find out more about the guest bloggers’ research (and pets!).

Hello Sir

Thanks for sharing the great information. I read this blog and must say the information that you shared in this blog is really very useful. Please post more blog related to “pet store”. It would be really helpful for those people who want to adopt a pet in Australia.

Thank You.